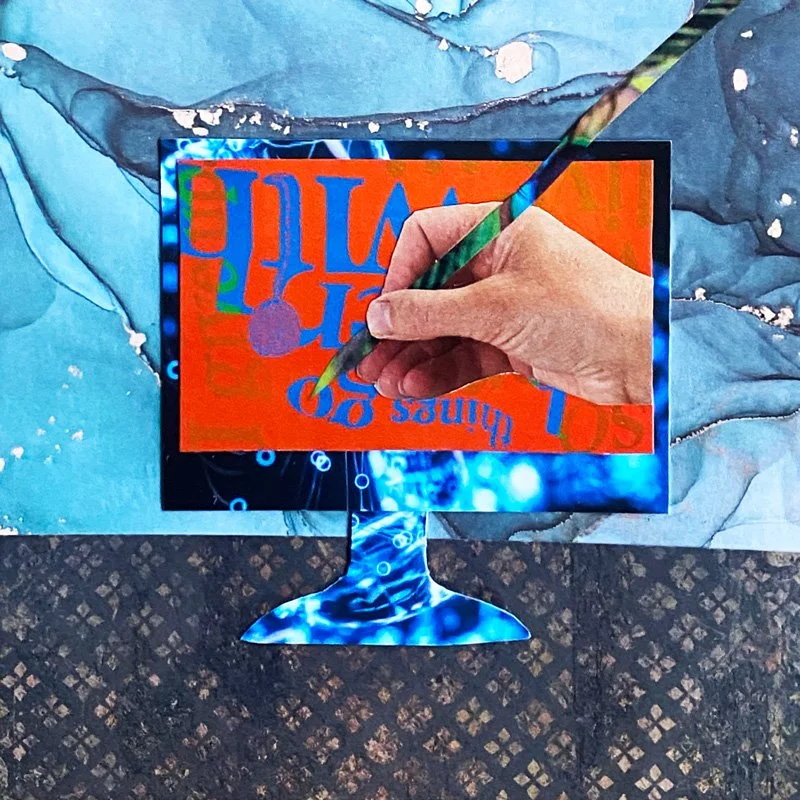

Just two months after launching Helen’s Word on Substack, I’ve found that locking away my essays and experiments behind a paywall doesn’t sit well with me — so I’ve flung the gates of my Writing Garden wide open. Even if you’re a free subscriber, you can now find the full texts of all recent posts on my Substack homepage and here on my website blog.

To my precious paid subscribers, including my entire WriteSPACE community: thank you for your continuing support!

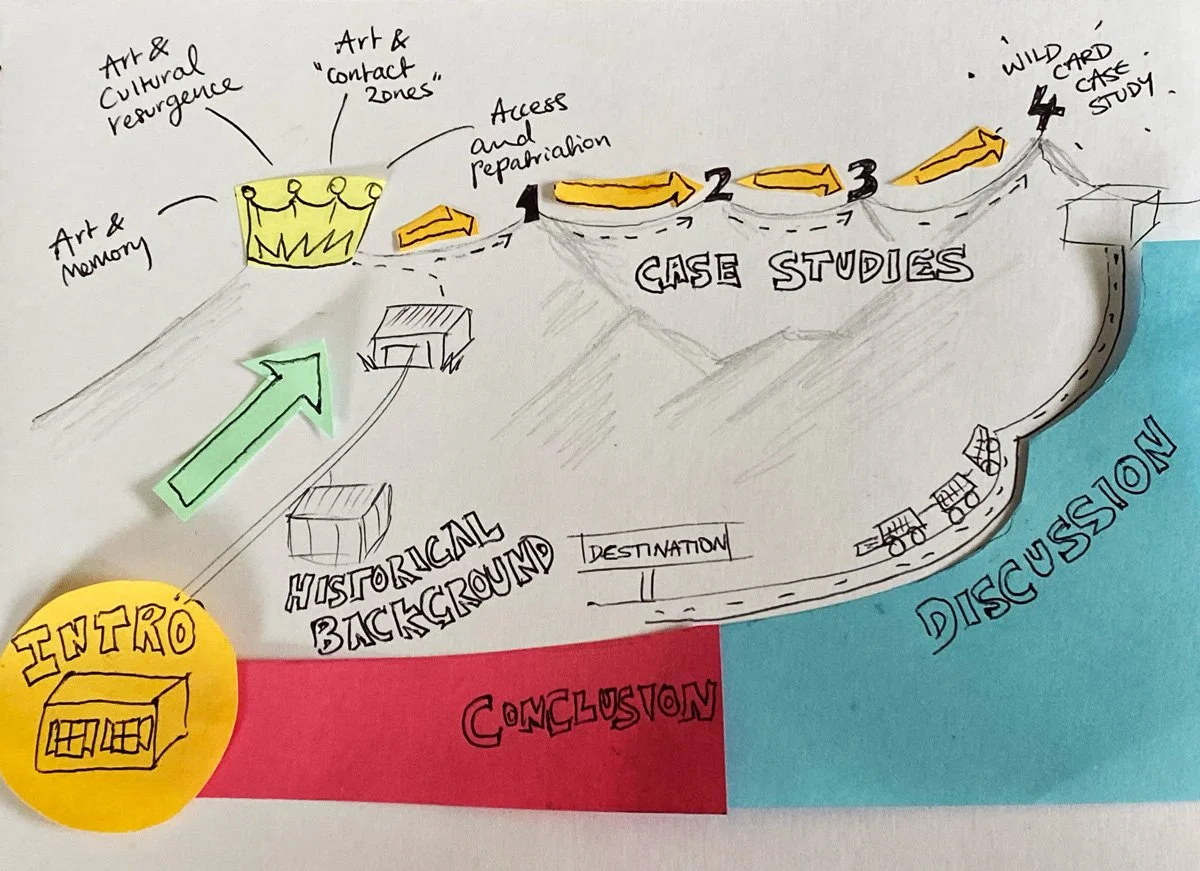

Moving forward, I plan to publish a series of monthly podcasts called “Swordswings”: short, easy-to-digest audio snippets in which I’ll address readers’ questions about writing and wordcraft. My very first Swordswing, coming up in early October, will respond to a query from Stephanie, a PhD student in Art History in Australia:

I am looking for some exercises / information / instructionals on how to write good transitions: I particularly struggle with the transitions between the big movements in my argument and sections within chapters. I am keen to read or watch any articles, books, etc that you could recommend.

These podcasts will be available to paid subscribers only. There are three ways to get access:

Sign up for a monthly or annual paid subscription to Helen’s Word ($5/mo or $50/yr).

BEST VALUE: Sign up for an annual WriteSPACE subscription ($150/yr), which includes unlimited access to hundreds of extra writing resources, weekly prompts, live workshops, and exclusive tools, all for just $12.50/mo.

Sign up for a monthly WriteSPACE subscription for $15/mo, or $45/mo if you choose the premium WS Studio plan. Click the button below for a free 30-day trial.

I’d love to see you there on the other side the playwall.

Be dramatic!

This week, in the “Be dramatic” module of my 6-week Creativity Catalyst, we’ve been playing with ways of bringing dramatic elements and techniques such as dialogue, roleplay, and theatrical staging into our daily lives, our writing lives, and our personal and professional writing.

I’ve been laughing out loud (and sometimes crying, too) reading the brilliant experiments that the course participants have been sharing in the online forum. It’s been so inspiring to watch these brave academic and professional writers pushing themselves so far outside their creative comfort zone!

Imagine presenting the Results section of your design education article as a series of children’s games from a Brueghel painting; or exploring theories of identity via a creepy carnivalesque drama dubbed Identity Theatre; or staging a conversation at a philately conference between stuck-up characters called General Duffer and Dr. Smartyskirt.

Pam, a social work researcher in Australia, was generous enough to allow me to print in full a satirical piece that she wrote, as she put it, in “a moment of frivolity” while responding to a Creativity Catalyst prompt called “Stage a Scene”:

Write about your research in the form of a screenplay or stage script. Describe the setting, props, and costumes; write dialogue for your characters; specify stage directions, camera angles, lighting, and sound effects. What famous actors would you recruit to play the lead characters in the movie of your research? Could it be adapted into a Broadway musical?

Enjoy!

STAYING ALIVE: A comedic drama in one part

Setting

A cold hard pavement near a busy road. Discarded papers blow about in the gritty breeze. Laughter, singing, shouting, and occasional applause can be heard intermittently in the background.

A thesis (dissertation) lies gasping on the footpath. People rush past on either side, intent on their own research, teaching, service . . . barely pausing to notice the near-death experience happening at their feet.

Soundtack

The soundtrack to this scene is “Staying Alive” by the Bee Gees. The Bee Gees have been around for a long time and some of the group have passed into a different life, and yet they still have some influence. It is not accidental that First Aid teachers use this track to help people learn the correct rate of compressions in CPR.

Props

The set is sparse and unwelcoming. There are few props — just a battered rubbish bin and a single streetlight. The set's colour scheme is monochromatic, inspired by brutalist architecture in many shades of grey.

Costumes

The thesis is wearing a royal blue coat, with silver details and a classy ribbon that matches the coat. Pam is in her pyjamas from waist down, but wears a neutral top and has brushed her hair and applied just enough makeup to keep people from telling her she looks tired. The First Aid team (Helen, Amy and Victoria) are in exuberant contrast: they are wearing bright colours, streamers and ribbons in their hair, with dramatically confident stage makeup. The cast of onlookers who stop to offer assistance are a varied bunch, their costumes ranging from tender pinks to vivid purples, one cast member in artistic black setting off the bright burnished orange of another’s outfit.

Lighting

The action takes place in the glare of the single streetlight, with the background movement taking place in subdued shadows.

Staging

The audience is seated a little distance away from the stage, grouped in various seating positions, and looking up at the elevated ivory-hued stage. A long delay occurs between the curtain going up and the start of any action, and the audience becomes restless. A few start to move towards the door, having little patience for academic/dramatic processes.

Scene 1

[The thesis is lying awkwardly on the pavement, one arm raised to attract attention, while shadowy crowds bustle to and fro in the background.]

Thesis (gasps): Help! Help! Please, someone...down here. I can’t hold on much longer.

Pam: Oh my goodness, it’s you! Thesis! What happened!

Thesis: I’m getting old and frail. I haven’t been getting enough sunlight. I haven’t had much exercise and I’m suffering from neglect, as you can probably tell. Where did you go?

Pam: I got caught up in marking! I feel so bad about this, but I had to earn a living, and, academia, you know . . .

[Pam clutches her pearls]

Thesis: Hack, cough, splutter.

Pam: Someone! Call an ambulance! There isn’t much time!

[Pam remembers her own phone, and dials frantically.]

Thesis: I’m so glad you’re back, though. If I don’t make it, promise me you’ll do something with our work. All those parents who shared their stories . . .

Pam: No, you mustn’t talk like that! We can still get something happening. I just need some fresh ideas.

Thesis: Maybe we should try to . . .

[The thesis collapses in Pam’s arms.]

Pam: No! I won’t let it happen! I will resuscitate you!

[In the distance, approaching sirens can be heard.]

Pam: Someone help! Why isn’t anyone paying any attention?

[A bystander pauses and speaks in Pam’s ear.]

Pam: Yes, yes, I know the marks are due in tomorrow. I know the university’s international ranking depends on student experience. I know I need to respond to the staff satisfaction survey and give my email address on the last page and of course I’m confident that all data is treated with the utmost confidentiality and no adverse employment consequences will occur. But Thesis is dying here! Help me roll it on to its back and start CPR!

[The bystander shakes their head sadly and moves back into the crowd. At this moment, an ambulance screeches to a stop at the edge of the stage, and Helen, Amy and Victoria jump out.]

Helen: It’s ok, we know what to do. Amy, Victoria, bring the tools!

Pam: Oh my goodness, how colourful! How vibrant! I feel a new energy. I might even break into dance!

[Other Creativity Catalyst classmates emerge from the crowd. One offers refreshment. Another calls encouragingly from the sidelines. A third passes a new tool to Helen and the group cheers.]

Thesis: Wha..? Where…? Who…? Oh, I’m feeling a little better. The creative energy is reviving me! Pam, we should start to work together again!

[The cast line up across the stage and in unison strike a pose, pointing with one extended arm to the sky. They break into song.]

All: Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah! Staying alive, staying alive! Ah, ah, ah, ah, staying aliiiiiiive!

[The curtains close, to rapturous applause.]

You may have recognized several of the characters in Pam’s drama as members of my indomitable WriteSPACE Team. My only disappointment is that Freddie, our Cuddles Manager, didn’t get to join us to help save the day.

This post was originally published on my free Substack newsletter, Helen’s Word. Subscribe here to access my full Substack archive and get weekly writing-related news and inspiration delivered straight to your inbox.

WriteSPACE members enjoy a complimentary subscription to Helen’s Word as part of their membership, which costs just USD $12.50 per month on the annual plan. Not a member? Sign up now for a free 30-day trial!