✨Star Navigation

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them [. . .]

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

—Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

When we stand outside and look up at the stars, we cannot help feeling that we are a part of something much greater than ourselves, a mysterious cosmic dance that cannot be fully captured in human language or explained by the charts of the learned astronomer. At the same time, that “mystical moist night-air” touches our minds and bodies with a kind of astral intimacy, conveying messages that seem intended just for us.

The writing process can feel like that too sometimes: intimate, overwhelming, and altogether too vast and complex to comprehend. Whether we face that process on our own or in the company of others, we are all adventurers making our way in the dark.

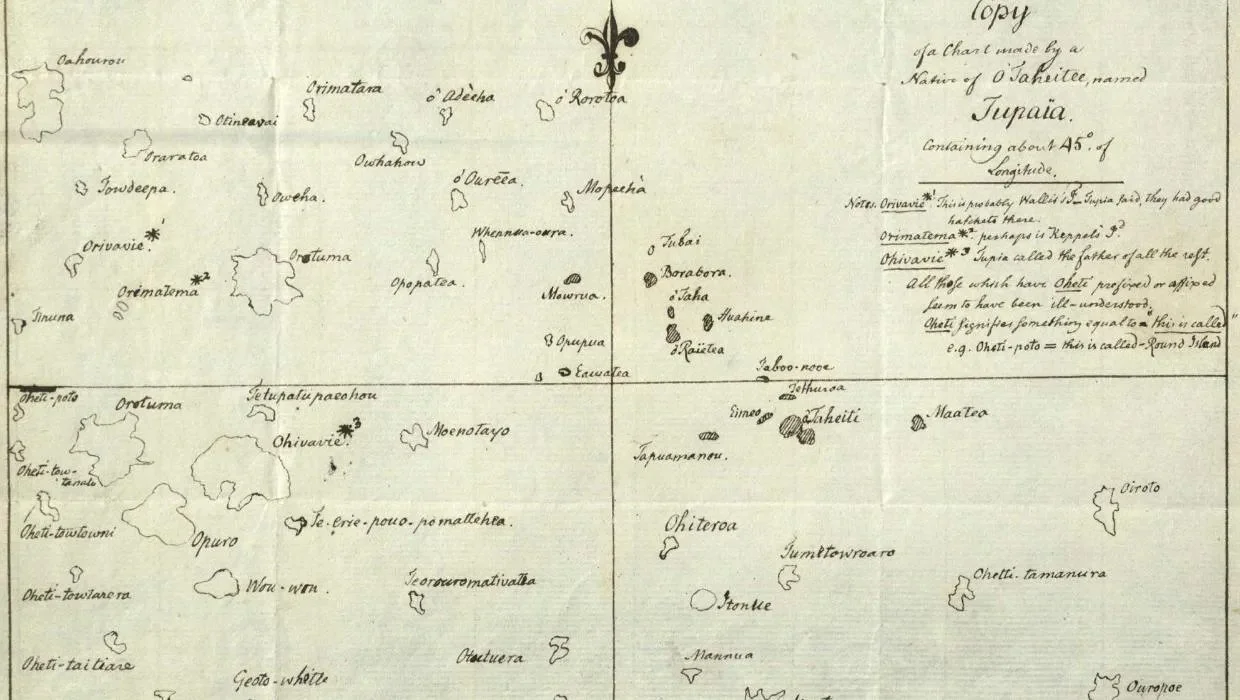

Tupaia, the Tahitian celestial navigator who sailed with Captain James Cook on his first voyage to the South Pacific, did not find his way by starlight alone; he also knew how to read the swell of the ocean currents, the drift of the wind, the cries of the seabirds wheeling overhead, the types of fish that the sailors landed in their nets, and the texture of the seaweed that trailed from their bow. Tupaia’s extraordinary knowledge of the locations of surrounding islands—many of them hundreds of miles away—was recorded on a map that subsequent commentators labeled “primitive” because the relational network it conveyed did not employ European conventions of plotting directionality from north to south.

Tupaia’s map of the South Pacific, drawn by Captain Cook and others on board the Endeavor, makes perfect sense if you read it based on a Polynesian worldview .

Similarly, it took European sailors more than two centuries to realize that the intricate rebbelib (stick charts) used by Marshall Islanders as navigational aids are designed to map the intensity of the ocean swells between neighboring islands, not their relative distance or location.

A rebbelib housed at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. (Credit: Cullen328)

Such stories of colonial myopia offer powerful lessons for writers from any culture. To a stranger, our own personal rebbelib might look like a chaotic jumble of sticks and shells. For us, it shows the way home.

Rebbelib drawing by Selina Tusitala Marsh for Writing with Pleasure

Take another look at the collage at the top of this post. What do you see there: a sun, a star, a compass? What other shapes and patterns do you notice when you allow your eyes to soften and linger? Amongst all the straight lines and curved lines, the sunbursts and spirals, what pathways can you trace — real, imagined, or desired?

In nearly two decades of writing about writing, I’ve learned the folly of pointing any writer down a single unidirectional pathway towards meaningful writing: for example, towards productivity or style or community or pleasure. The compass rose of writing offers us not a set of stark choices — north or south or east or west — but a starburst of possibilities, a dynamic creative field.

If you’re an academic or professional writer still trying to find your way, check out my new WriteSPACE Journey Planner. I’ll help you chart a route and itinerary tailored just for you.

Kia pai tō koutou rā (have a great day) – and keep on writing!

Subscribe here to Helen’s Word on Substack to access the full Substack archive and receive weekly subscriber-only newsletters. WriteSPACE members enjoy a complimentary subscription to Helen’s Word as part of their membership plan (USD $15/month or $135/year).