Crossing the Alps

We’ve been “making stuff” in the Creativity Catalyst all this week, which has inspired me to lean with extra energy and attention into making the paper collage that heads up today’s newsletter.

I approach the process differently every week. Sometimes I already have a topic in mind, so I let the title or theme dictate the design. Right now, for example, I’m mulling over the collage options for my upcoming WriteSPACE Special Event on Writing and Risktaking with criminologist David R. Goyes. Should I create a recognizable scene — a mountain climber scaling a cliff, for example, or a ringmaster placing their head in a lion’s mouth — or use abstract images to invoke an emotional response? Will I incorporate words amongst the images? What does risky writing look like, anyway?

More rarely, I start with the collage and let the writing follow. Perhaps I’ll begin with a word or image and build the collage from there. Or maybe I’ll pull out paper and scissors and glue and just start playing around: cutting pictures from magazines and books, juxtaposing colors and textures, waiting for the moment when the collage show me where it’s taking me. I love this part of the process, which never fails me. Bit by bit, under my moving hands, a colorful conglomeration of images takes shape — and as it does, I’m thinking about how and what I’ll write to go with my new collage.

Below you’ll find my visual-verbal narration of how this week’s image came into being. I’ll end with a few writing/collage prompts that you can try for yourself.

Enjoy!

The Simplon Pass

Many years ago, when I was a PhD student in comparative literature, I read Wordsworth’s masterpiece The Prelude, or Growth of a Poet’s Mind in a graduate seminar on Romantic poetry. Our professor pointed out the famous scene — sometimes published as a free-standing poem called “The Simplon Pass” — in which the young poet experiences a kind of sublime epiphany, a perception of divine Eternity in the ever-changing features of nature:

The immeasurable height

Of woods decaying, never to be decayed,

The stationary blasts of waterfalls,

And in the narrow rent, at every turn,

Winds thwarting winds bewildered and forlorn,

The torrents shooting from the clear blue sky,

The rocks that muttered close upon our ears,

Black drizzling crags that spake by the wayside

As if a voice were in them, the sick sight

And giddy prospect of the raving stream,

The unfettered clouds and region of the heavens,

Tumult and peace, the darkness and the light—

Were all like workings of one mind, the features

Of the same face, blossoms upon one tree,

Characters of the great Apocalypse,

The types and symbols of Eternity,

Of first and last, and midst, and without end.

But shortly before this revelation, Wordsworth narrates a scene of bitter disappointment, almost as though the former required the latter for its release. Having become separated from the rest of their group while crossing the Alps between Switzerland and Italy, the poet and his companion attempt to scale a lofty mountain, get hopelessly lost, and have to backtrack. Eventually they meet a local peasant who points out the route to their destination, which leads inexorably downward:

Loth to believe what we so grieved to hear,

For still we had hopes that pointed to the clouds,

We questioned him again, and yet again;

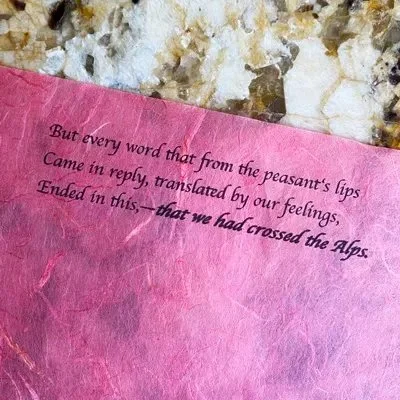

But every word that from the peasant's lips

Came in reply, translated by our feelings,

Ended in this,—that we had crossed the Alps.

The mountains of the mind

Using italic font in several different sizes, I printed excerpts from the “crossing the Alps” stanza on collage paper of various shades and textures, pondering as I did so the central question of Wordsworth’s poem: What does it mean to cross the Alps unknowingly, missing out on that key moment of summiting? If you undergo a major life transition without noticing it, can you really count it as a milestone?

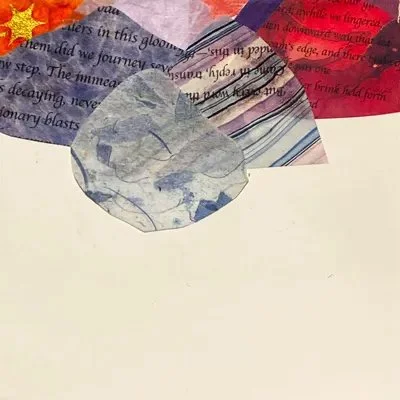

Opening myself to the wisdom of what Ursula K. Le Guin calls handmind, I started cutting and layering the paper, trusting my hands to tell me what to do. Before long, I noticed mountains forming:

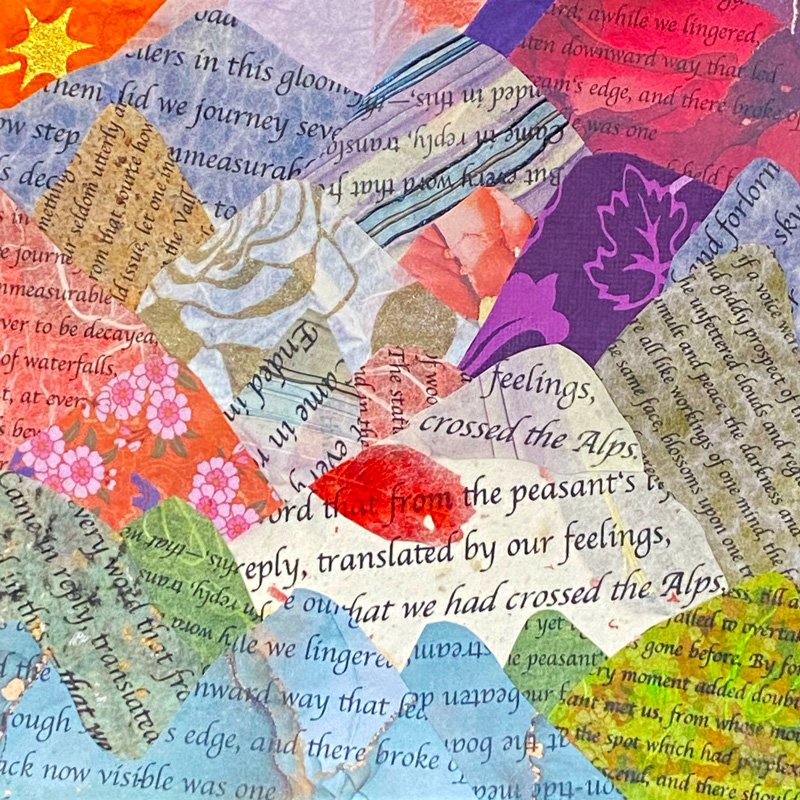

My collage, I decided, would depict a mountain range criss-crossed by tracks of text. My placement of each “mountain” was dictated — no, that’s too strong a word, it was suggested — by some ineffable combination of color, pattern, texture, and text. Some of the words ended up upside down, or they slanted sideways like layers of sandstone shifted by ancient earthquakes:

I decided not to use the pink sheet on which I had printed out the poem’s key message in bolded, extra-italicized text, as it seemed a bit too in-your-face:

But I did make sure that the phrase “we had crossed the Alps” appears in a prominent position on the white mountain in the foreground of the collage:

And when my composition was all but complete, I capped that white mountain with another iteration of the same phrase, carefully centering feelings at the peak of the mountain and crossed the Alps just below:

All that remained for me then was to photograph the finished collage in better light and play around with the color mix in Photoshop, so that the finished artwork glows on your screen as though backlit by bright mountain light:

Have you ever fixed your eyes on a real or metaphorical mountain and, in doing so, lost sight of the path you’re actually walking on? Have you ever looked back on a transformational moment in your life and realized that you failed to notice it at the time because you were focusing on the wrong things? Like Wordsworth’s poem, my poem chronicles the challenges of looking, travelling, noticing, aspiring — the central themes of any writer’s life.

Coming down the mountain

If you’d like to try this writing-and-collage exercise for yourself, here are a few prompts to get you going:

Choose a short passage of text to work with: for example a poem or song lyric, a paragraph by a favorite author, or a piece of your own writing.

Copy or print the text out on sheets of colored or patterned paper, using different fonts and font sizes if you wish. As you do so, think about why you’ve chosen this particular text and what you can learn from attending to it closely.

Cut or tear the paper into scraps or shapes and start arranging them on a piece of cardboard — anything strong enough to remain stiff even when you covered with wet glue.(I use square 15x15 cm pieces of canvas or card stock, but any size or shape will do). Think about what you’re doing and why as you make your decisions about composition, imagery, and form, but don’t overthink.

When you feel ready, start gluing the paper onto the cardboard using white glue or a glue stick. Don’t worry if you make mistakes or affix things in the “wrong place” (whatever that means!) Mistakes can lead to serendipitous flashes of insight.

To finish off, you can frame and display your collage, or glue it into a notebook, or photograph it and post it on Instagram — or not! In collage-making, the process matters as much as the product.

Don’t forget to write! Before, during, after the collage-making process — in your head if not on paper. Your handmind will tell you what to do.

This post was originally published on my free Substack newsletter, Helen’s Word. Subscribe here to access my full Substack archive and get weekly writing-related news and inspiration delivered straight to your inbox.

WriteSPACE members enjoy a complimentary subscription to Helen’s Word as part of their membership, which costs just USD $12.50 per month on the annual plan. Not a member? Sign up now for a free 30-day trial!