Containers for Chaos

Writing with Pleasure was published by Princeton University Press exactly one year ago. If you missed my virtual book launch on Valentine’s Day 2023, featuring ebullient poet-illustrator Selina Tusitala Marsh and legendary PUP editor Peter Dougherty, you can watch the video replay here.

It took me six years to bring this buoyant book into the world — and yes, I experienced plenty of stumbles and grumbles along the way. But pleasure, I’ve learned, is an emotion contoured by shadows as well as light. No mud, no lotus.

Some days, I’ll confess, all I could see was the mud. My data set included 590 handwritten narratives of pleasure gathered from academic writers around the world; thousands of individual notes and quotes; millions of combinatory possibilities. So much information, so many swirling ideas! How could I make sense of them all for myself, let alone for my readers?

Fortunately, my research on productivity and pleasure equipped me with many creative strategies for bringing curiousity, playfulness, and joy to my writing. One that I turned to again and again was a technique I call “Containers for Chaos”: an iterative process of meaning-making that shifts back and forth between conceptual and material modes. It’s an intensively intellectual activity informed by physical acts of seeing, making, and doing.

Here are three Containers for Chaos that helped me find the shape of my book and the flow of my writing.

Enjoy!

Scrivening

Picture a long wooden table cluttered with piles of pdf printouts, handwritten notes, interview transcripts, rough drafts, notecards, post-it notes, photos, DVDs, ideas scribbled on cafe receipts — you get the idea. Next, imagine a row of colorful milk crates beside the table, each labelled with a potential chapter topic or title. As you sift through the items on the table, you toss each one into the box where you think it belongs, gradually accumulating all the materials you’ll need to support your arguments for each section of your writing project.

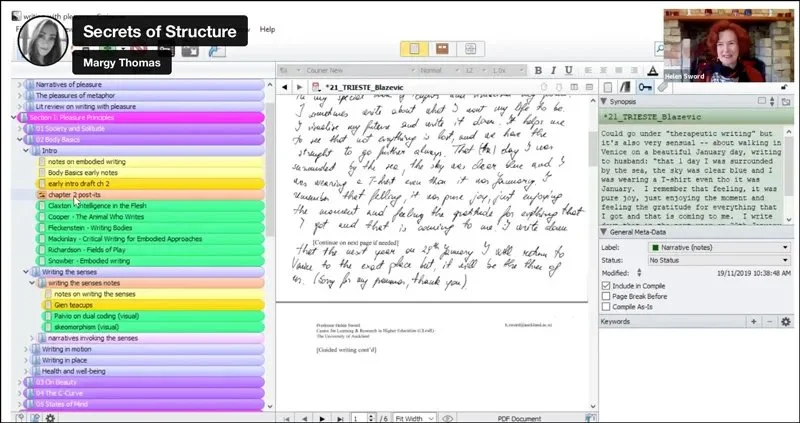

That’s how I used Scrivener, a proprietary software program beloved by many academic writers despite its steep learning curve. This screenshot of my Scrivener console comes from the video replay of The Secrets of Structure, a live Zoom conversation that I held with developmental editor and ScholarShape founder Margy Thomas in September 2020, when Writing with Pleasure was still very much a work in progress.

Yes, I would have preferred the chunky materiality of a real wooden table, a real set of milk crates, real piles of real documents with crinkled edges and smudged ink. But the multimodal affordances of Scrivener — the color-coded labels, the scanned handwritten texts, the virtual index cards — helped me contain the chaos of my complex materials in a satisfyingly creative, visceral, non-linear way, with all the added benefits of digitized searching, effortless cutting-and-pasting, and efficient storage.

Fractals

Much though I enjoyed working with Scrivener, I still needed an occasional break from keyboard and screen, a return to the material pleasures of paper, pen, and glue.

One day, following an intriguing conversation with Margy about her Story-Argument model — which offers a way of conceptualizing a scholarly project based on macro, meso, and micro levels of meaning — I decided to map out the story-argument of my book, chapter by chapter and section by section. In joyful anticipation of the task, I gathered some colorful materials that I already had to hand and laid them out on my carpet: a book of Indonesian wrapping paper designs; a stack of post-it notes; a fountain pen filled with turquoise ink.

The image above captures my mapping of the first two chapters: Chapter 1 “Society and Solitude” and Chapter 2 “Body Basics.” On each of the two facing pages, I’ve stuck nine square post-it notes that record the following information:

The One Essential Idea (OEI) of the chapter.

The Hook that will draw my readers in and the Revelation that will inspire them.

The Hook and Revelation for each of the chapter’s three sections.

Three key Units of Meaning (UoM) for each section:

The Claim that will make my reader think, “Oh, really? Prove it!”

The Evidence that will persuade them.

My Interpretation and Analysis of that evidence.

The Complications and Caveats that I need to keep in mind.

Smaller post-it notes suggest possible topics for the three illustrated panels in each chapter (“The Pleasures of . . .”) as well as further areas for research.

The visual, tactile process of assembling this Container for Chaos proved intensely pleasurable for me, both intellectually and creatively. The entire project took me no more than a few hours. And by the time I had finished, I understood with a new intimacy and clarity the fractal nature of my book, which started from One Essential Idea — “Academic writers can and should write with pleasure!” — that radiated out into every chapter, every section, and every illustration.

Mosaics

Another Container for Chaos was the mosaic mirror on the wall of my study, which became a sort of talisman for me, a visual representation of the aesthetically beautiful, intellectually complex work that I wanted my book to be. In my Preface, “The Mosaic Mirror,” I recalled how I created the mirror from a curated collection of fragments:

I remember the first time I crafted a mosaic mirror, the one that now hangs in my study. I had already spent a long time assembling its constituent pieces and sorting them into containers: shards of stained glass in rich blues, purples, and greens; sea glass worn smooth and opaque by the waves; seashells and broken pieces of mirror; colorful glass nuggets with flat bottoms and domed tops. I laid out all my materials on my dining room table and began positioning them on a large piece of particleboard around a smaller square mirror at the center: fragments of glass and shell arranged randomly but not capriciously in flowing drifts of light, each set off by the color, shape, and texture of the others.

Describing the structural design of the book, I reflected on the anxieties I felt about publishing such an unconventional piece of scholarship:

The treasures I have laid out here are at least as precious and varied as those bits of stained glass, mirror, and shell, but much more hard-won: first-person narratives of pleasure contributed by hundreds of writers from many different countries; books and articles from a wide range of research disciplines; excerpts from my own poetry and experimental prose; original artwork by my friend and colleague Selina Tusitala Marsh—all broken up into colorful fragments that I arranged with a similar sense of self-confidence mingled with dread. Have I got the balance right? Do I dare to glue them down? Is the grout between them bland enough to set off each independent element yet also strong enough to anchor them in place?

Selina’s artwork beautifully captured the playful mosaic-like energy of the book, reminding us that the pleasures of both writing and reading extend far beyond the march of black letters across a stark field of white:

If you are the kind of reader who likes to start by reading the preface of a book and working your way straight through to the afterword, feel free to set my mosaic metaphor aside and progress along the linear path laid out in the table of contents, which will offer you safe passage. But if you would like to try out a more creative, intuitive, nonlinear style of reading, I invite you to approach this book as you would a mosaic mirror on a gallery wall, first stepping back to take in the whole composition, then moving in close to absorb its colors and touch its textures in whatever order you please.

Each of these Containers for Chaos — my Scrivener project file, my book of fractal logic, my mosaic mirror — helped me find my way to the final structure and shape of Writing with Pleasure. At the same time, each container held its own little universe of colorful chaos: capacious enough to absorb new ideas, flexible enough to allow for experimentation and play.

Perhaps life itself is a Container for Chaos?

Subscribe here to Helen’s Word on Substack to access the full Substack archive and receive weekly subscriber-only newsletters. WriteSPACE members enjoy a complimentary subscription to Helen’s Word as part of their membership plan (USD $15/month or $135/year).