The Notebook Walk

Transcript of Helen Sword’s podcast episode The Notebook Walk

Hi, I'm Helen Sword from HelenSword.com, and this is Sword Swings, my podcast series for writers in motion. Whether you're driving or on a train or a bus or just out for a walk, this recording will help you move yourself and your writing to someplace new.

For today's podcast episode, we're exploring the note-taking practices of some famous figures, including Julia Child, Carl Jung, John Milton, George Eliot, Toni Morrison, and Sylvia Plath. Let's jump into my conversation with Jillian Hess, author of the popular Substack newsletter, Noted. Together we discuss new forms of writing and contemplate how to draw inspiration from other writers' notebooks.

…..

Helen: So Jillian, I'm going to ask you what I always ask my guests as the very first thing, which is, can you just give us your intellectual autobiography? That sounds very weighty, but I'm really interested to hear how you got to where you are in your career and in your newsletter. Yeah.

Jillian: Sure. Well, first, I just want to say thank you so much, Helen, for inviting me. I'm such a fangirl of yours. So this is so exciting. I think writing on Substack has given me so much, but the ability to connect with people like you is really beyond what I ever expected. And then also, I just wanted to thank, I see some regular readers of Noted, my Substack out there. So thank you so much for coming. And it's lovely to see some of your faces for the first time.

So my intellectual biography…So I think like many of us, I just loved reading. I was obsessed with literature, and I felt like I had this very deep connection with it that I wanted to memorialize in some way that I was reading literature that I loved, and I wanted to find a way to kind of collect parts of it for myself. So I started a notebook of quotations.

So just quotations of the books that I was reading at the time and my favorite quotes. And this was around middle school. And I continued doing this through high school and college. Then, when I got to Stanford, which is where I got my PhD, I enrolled in all of these courses that gave me access to special collections. So to the libraries with all of these really old books and manuscripts. And what I found was that there were so many notebooks with collections of quotations from hundreds of years ago. And that this thing that I had been doing thinking was just, you know, my own little quirk of collecting quotations was actually this really old and theorized tradition, which is called the commonplace book tradition. So that's what I ended up writing my dissertation on. And that turned into my academic book, which came out exactly a year ago. So November 2022.

And the title is How Romantics and Victorians Organized Information: Commonplace Books, Scrapbooks, and Albums. And I had so much fun writing it because I was able to go to libraries all over the world and do all of this research. And I felt like I had learned a lot about note-taking that perhaps a non-academic audience might be interested in. So I decided I'll start a Substack, and I will feature a different note-taker every week because this is not this is not an academic project anymore, I don't have to stay within my field, which is romanticism and Victorian literature. I can branch out! I can write about artists and musicians and scientists and chefs. And I also don't have to stay within the 19th century. So to me, writing on Substack has just been incredibly liberating because I just follow my curiosity. So anyone that I'm interested in learning more about, I can write about them.

Helen: And you don't have to go to archives anymore either, do you? I mean, obviously you love archives and would like to, but you've got some of your posts that you've drawn mainly from... biographies and things like that.

Jillian: Yeah, it's so… Certainly when I started my dissertation, there was hardly anything online. I could never have done this. It was like in 2007, a long time ago. And it is true that because I teach, I'm a community college professor in the Bronx at Bronx Community College. So I am in New York most of the time and very busy with that. So I don't have as much time to go visiting archives as I would like. But at the same time, there's really truly a lot that is not digitized. Something that I've just been thinking a lot about, because we all know that archives are representations of what we as a culture value and the kinds of people that have digitized notes tend to be more established types of people. so I do feel like going to the archives is something that is really important and something that I still continue. I'm going, I'm doing more of because there are people like, for example, Audrey Lorde, her papers are not digitized. So I need to go to Atlanta to see them. Or someone like Gloria Anzaldúa, who I love. Her papers are also not digitized. So, I could definitely continue writing Noted without visiting any archives because there's so much that's online, but I still think that for the fuller picture of what notes are, the archival research is still an important component.

Helen: Well, there's also an in-between, isn't there, which is the library, right? So you have lots of things that are, that have been collected in books. You know, I'm, I'm, thinking of these like additions of things like T.S. Eliot's Wasteland, there's the version with the whole, the typescripts, the manuscripts, Ezra Pound's notes, all that kind of stuff.

And you can get that out of the library and photograph, presumably those pages. It's the kind of thing that Maria Popova, if you know her newsletter, Marginalian, you know, she's been doing it for years, going and finding things in libraries and sort of bringing them out into the digitized world.

So it's an interesting conversation, isn't it, with these texts and their different forms.

Jillian: Yeah, and I just wrote about Frankenstein, Mary Shelley's notes on Frankenstein. And that I did not have to go to an archive for. I did have to go to a library because there are printed editions of her notes.

Helen: And you say you follow your curiosity. Are you also getting suggestions now from your readers? People saying, ‘oh, you must go and see this and see that’ ?

Jillian: Absolutely. Yeah, I love that. Yeah, that's my favorite.

Helen: So one thing that Noted has really opened up for me is realizing how many different kinds of notes and notebooks there are. I called this [interview] ‘Writers and their notebooks’ to try to narrow things down a little bit or just to kind of be a bit thematic. But a lot of the things you write about aren't notebooks at all. You know, they might be note cards or memos or other ways of, organizing information a lot of them aren't about organizing information are they? They're about thinking through note taking and so they're not necessarily composed into anything. And then notebooks themselves take an astonishing variety. So without wanting to put you on the spot too much, can you rattle through some of the varieties of, let's just say, note-taking practices maybe that you've come across?

Jillian: So I think the first... is the commonplace book, which is the collection of quotations and often, but not always, often there's an index. So this is John Milton's commonplace book and his page on kings, Rex, the Latin word for kings. And then he has indexed it. So the commonplace book as just a repository of quotations and ideas is kind of the one I always think of. But I think the commonplace book can also become this sort of nesting place for incubating ideas. And this is one of my favorite pages. This is George Eliot's, one of George Eliot's commonplace books.

And you could see her coming to the name of one of her characters. So she writes Spencer, born 1552, 12 years older than Shakespeare. And then curious to turn from Shakespeare to Isaac Casabon, who as many of you know, is the name of one of the characters in Middlemarch.

So there are these moments where authors are just writing out information, but then it seems to spark something that leads to a bigger idea. So those are just a few examples of commonplace books. I also found a lot of process notes. So this is from Octavia Butler's archive at the Huntington Library. And she's another one I had to go to the Huntington Library to see these because they're not digitized yet. Although, hopefully, one day, they will be. But she was someone who spent a lot of time kind of coaching herself and inspiring herself. And so this is these are her tips for becoming a successful writing a successful novel.

But then she also would have these contracts with herself of, ‘I'm going to write 20 pages today.’ But then these process notes of asking herself questions. So the questions are in red. And then her answers to these questions are in blue and black.

Helen: Let's see. Oh, my God. Some of these make me feel so inadequate, right? Yeah. You know, it's like, I don't spend hours a day writing about what are the goals of life and what is death and finding quotes and cross-referencing this.

Jillian: Yeah, I think... I think a lot of it, though, really depends on what you need. And this was something that Butler really felt she needed because she didn't have a lot of encouragement early in her career. And she was working class. And so she had all these she had jobs that she was in throughout most of the day. So she would get up at 3 a.m. every day to get her writing in before going to work. So she needed a lot of this encouragement that she gave to herself because no one else was doing it until she became very famous and successful. And then a lot of people gave her encouragement. I think we all need very different things from our notebooks. You know, and then I'll give you maybe another example, which is Toni Morrison's drafts for Beloved. And she did do she did a lot of research. So she typed up annotated bibliographies, which I think is such an important tool to it's not just reading and it's not just writing out quotes, but it's also synthesizing. and turning it into a different format, like an annotated bibliography paragraph.

Helen: So what we're seeing here in several of these examples are very much process notes towards a finished product. And that, of course, is where, I mean, you're a literary scholar, so am I. This was always a part of my training, right?

This was why you went into archives, not to see the messy notes, really, but to see the process.

I still remember writing about Yates's Leda and the Swan and you go and you look at his early drafts, you know, and it starts out with this sort of a hovering and a… It's very sort of tentative, and it takes him, I've forgotten how many drafts to get to “A sudden blow, the great wings beating still” you know, and it teaches you something then about the importance of, I guess, patience and process and things like that.

So that's a kind of a teleological reading of these notes, I guess, where we already know what the end point of them is, so we like to go back through Beloved and say, oh, she did it. She thought about this, she did that, right?

Jillian: She started off with 124 was loud instead of spiteful right? yeah, I think about this often that it's a little bit easier for me to understand what's going on in notes that lead up to something that's published.

Whereas sometimes it's a little bit more challenging as a writer to know exactly what's going on in the messier notes, although they have their own beauty. And I'm not even sure if I included any in this PowerPoint of kind of messier notes.

Helen: Messy notes that you have no way of knowing what they're, what they're leading towards or whether they're leading towards anything.

Jillian: Yeah. But this actually, this is a really interesting question because often they're like these messy non notes that have nothing to do with the finished product or the published work. but like they're on the same page. So for example, just looking at Mary Shelley's diaries and her notes on Frankenstein for Frankenstein, I mean, they're all of these calculations, just like mathematical calculations on the sides. And I don't think that has anything to do with Frankenstein. There are definitely some authors who have these calculations because they're obsessed with word count.

Helen: But she was just doing a bit of mathematical doodling on the spare paper.

Jillian: Yeah, yeah. But I do notice my own tendency. It's just so much easier for me to write about notes that lead to something because there's already this narrative built in, which is not to say that the other notes aren't interesting. Yeah. But maybe another example of something... That isn't, it's not teleological: Sylvia Plath's diaries.

Helen: In so far as we know her biography, right?

Jillian: Yeah, yeah, yes.

Helen: It's the development of the person.

Jillian: And considering just how, you know, she's a confessional poet. You know, these are not diaries that end up becoming something, becoming the bell jar. These are from an earlier period in her life.

Helen: That is so much about the creation then of Sylvia Plath, the poet, you know, and I know when you wrote about her stuff before you wrote about some of her artwork and stuff. Did you, have you been to the archive in Bloomington where all of her Juvenilia is?

Jillian: No.

Helen: I used to teach there at Indiana University, and they had all of her. It's one of these things where there were two pieces of her estate, and they ended up in different places. And so I think there was all this stuff that ended up at Smith College that was more sort of her adult stuff.

But her Juvenilia, I think her mother sold it to the Lilly Library in Bloomington. And so it's all these paintings she did, like in college and stuff. And so they are not part of a known story of Sylvia Plath.

You know, we don't think of her as a visual artist, but you can see here in these notebooks that she was always, always drawing and painting. And it becomes just kind of an interesting addition or side note, I guess, to look at somebody like that. And it rounds out your image of them.

So these feel to me very much like Sylvia Plath self-fashioning. But then there are other bits of the archive that are very much, as you say, the teenager being herself for trying out different kinds of intellectual modes.

Jillian: Yeah. And then because of the way Noted has unfolded, it's about famous people for the most part. But then there are also all of these notes…So this is something from my book. And it's one of the first notebook/commonplace book/scrapbook that I looked at in graduate school. And it is an early modern commonplace book. So the writing underneath the images are, I think, from the 16th century. And the topics are in the margin. And then at some point in the early 19th century, someone takes over this book and starts pasting images on it. And you can imagine 200 pages like this of this really old handwriting.

And now it's just scrap paper for collecting all of these new printed materials coming out in the early 19th century. So this is an example of something that I have no idea who the person is, we have no idea who did this. The original owner and then whoever pasted the pictures on top, they're completely anonymous.

But it's part of this larger trend that we see in the 19th century of collecting images and collecting the scraps of print culture that have become affordable in a book of one's own.

Helen: But you could do that without pasting it on top of somebody else's writing. You could make a scrapbook where it just goes onto a blank page. So it's really interesting that they've chosen to do this and whether they've done it because they considered the original book to be junk and expendable or whether they do it because they actually see it as a worthy frame for these things? It's really interesting. It reminds me of those books, you know, people will buy old books and do these elaborate cutouts in them you know so you open them up or um you know there are lots of uses for old books that turn them into something else. And you could say it's a destruction of the book or you could say it's a refashioning into something, you know, it's the next round of art coming out of it. Interesting.

Jillian: Yeah, I would like to think that it's intentional because it's just so beautiful.

Helen: It is. It is. Yeah. It's like a palimpsest. It's got these layers. Yeah.

Jillian: I could keep going, but are there particular types of...

Helen: I'd love to have you scroll back to the Carl Jung one at the very beginning, those mandalas. That one, which you read about quite recently. So these are just kind of the sketches of them, but some of the things you published in your post then were these... incredibly elaborate painted things that he was doing. Was it every morning?

Jillian: This is one of the elaborate paintings that came out of his mandala work. Originally, Carl Jung was going through this period of what I think of as a midlife crisis. He had broken up with Freud, and he was afraid that he was about to have a psychotic break.

And so he kind of stepped away from his job as a professor, and every morning he would draw one of these mandalas. So just these geometric shapes. And these are the ones that he would draw in the mornings. So the elaborate, beautiful painted ones came later.

This is what he would do every morning. And it was a way of getting insight into his own internal world. And the one on the left, he describes this one as a day that he wasn't feeling quite right and so the mandala reflects this in that it's it's incomplete, it's not finished. So I brought I brought some of my own notebooks, and this is one. This is a practice that I started doing myself, so I'm a little embarrassed [laughs] because they're not very symmetrical, but I started doing this daily by just drawing shapes.

Helen: This is inspired by Jung, you're saying?

Jillian: Inspired by Jung, yeah.

Helen: I thought of doing something like that. I just haven't quite got there yet. So maybe this is going to be my moment to... So what's it doing for your brain?

Jillian: I think it gives me a moment of quietness when I'm not thinking about anything else. I mean, I'm not sure that they're reflections of my psychological state. Perhaps they are, but that's not why I'm doing them.

Helen: Do you write about them then or do you just do the drawing and move on?

Jillian: I just do the drawing. That's an interesting question because probably if I did start writing about them, I would get into some of the deeper psychological meanings…I imagine it's a little bit like tarot cards, like that what you interpret, what you pull out of it is the interesting thing, the more meaningful thing.

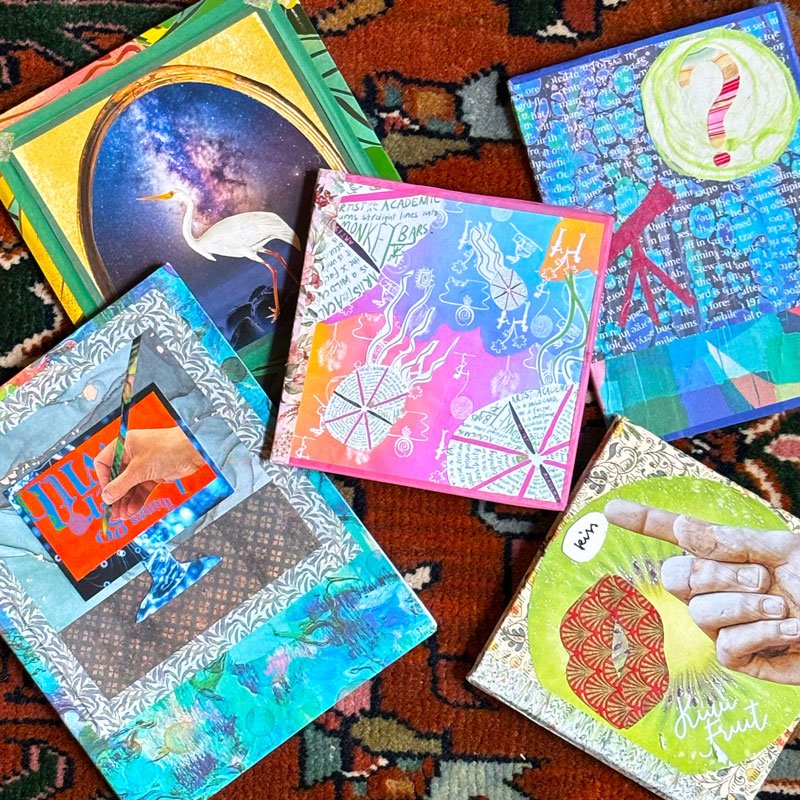

Helen: Drawing is such a meditative practice because you can be doing that and you can be thinking in words. Right? Writing, you can only think about the writing. But when you're drawing, you can have this parallel thinking going on. And so I do a lot of paper collage stuff. These kinds of things are because I put a new paper collage on every newsletter; this is the one I turned into a notebook inspired by Jillian. I was like, oh, now I know what I can do with all those paper collages I have sitting in a drawer. I'll make notebooks to write in really messy, messy notes. I'll fill this one in a week or two and then be done with it, but I won't want to throw it away. But when I'm making these, I'm sometimes I'm listening to an audio book or something, but sometimes I'm thinking about the newsletter I'm going to be writing. Sometimes I've already written the newsletter, so I'm thinking about what's an image that complements it. I don't want to do things that are too literalist. I usually sort of get an idea. But then there's a part of my brain that's just thinking about form and color. It's quite sort of absorbed in that. I've started trying to document that process a little more because I found people who are really interested in seeing the process of something like that. So what were the steps? Why did I make these decisions?

And yet there seems to be something about those sort of mandala objects that you're doing that's almost freed from that. You know, it's more the meditative practice like an adult coloring book or something. Jung seems to have been somewhere more at the... Well, I don't know, I'd be interested to know his practice, whether it was kind of meditation where he's trying to clear his mind, and then the meaning emerged, or whether as he was doing it, he was thinking, ‘I'm not feeling great today. So I'm going to do a truncated mandala.’ Did they tell him what he was thinking, or the other way around.

Jillian: Yeah, I'm not entirely sure, but I imagine it was part of his, I mean, so much of what he was doing at this time was trying to access a dream state while awake. And this is what he would do at night. He would sort of go into this trance and have these visions with all of these characters that just came out of his mind that would then escort him around his internal world and help him through what he called ‘a conversation with his soul’, ‘a confrontation with the soul’. So the mandala practice seems very similar to that, as a way of trying to get into this space that is what he described as between consciousness and unconsciousness.

Helen: It's yoga nidra, right? It's this making sleep sort of thing and then the mandala also very much from these eastern traditions. So this is a wonderful thing about, again, your newsletter. I'm learning these bits and pieces about people. I think of Jung as, you know, he's very Swiss. He's very Western. You think of archetypes and the archetypes are very culturally influenced.

I had him in a bit of a box, I have to say. It has been just opened up by this idea of him being, doing waking dreams and a mandala every morning. I'm finding myself thinking I've got to go and spend some time with Jung. It's really, really interesting.

Well, let me add, sticking with Jung, how did you find his notes? How did this become one of your objects to write about?

Jillian: So it always kind of had Jung in the back of my mind as a person that would be really fascinating because I went through a phase of just reading a lot of Jung when I was 16. And then actually, this is another example of a reader suggesting in the comments to some other post, I can't remember which one, someone said, you should check out Jung's Red Book, which is the illustrated version of all of these Yoga Nidra-like fantasies. That's how I came to him. And what I usually do is I search for their notebooks first to see if I can find them. And if they're interesting, if there's something that I can, that I feel would add something to the catalog on Noted. With young, I find this with most notes, honest, that like, the more you learn about a person behind the published and celebrated biography of what we know about the person, there's so much more! There's usually so much more depth.

I felt that way with Octavia Butler's notes too, that there's so much that we don't know because... We don't have access to all of these diaries and process notes, usually until after the person is gone and they've donated their works and their papers and they've been cataloged by libraries.

So notes almost always give us a very different perspective on a person because the published figure often becomes kind of reduced to these ideas, like the archetypes, which is fair because that's what he's known for. But that's not what he was necessarily obsessed with in his own personal life.

So the notes just give us a very different perspective.

Helen: It's just kind of rounding out, right, of these more human figures and messy notes. I mean, I guess that's where when I see the people with the really neat notes, I feel this kind of like anxiety and sort of anxiety. How can anybody do that? And I remember feeling that when I first read about bullet journaling, right? Where you have the whole index and everything leads to this and that. And I went and I got some bullet journals, and I tried to do it, and I had to at some point just admit to the fact that for me, taking notes is not about making my life neater and more organized. It's actually about my messy self, you know? Having a place to just think. So the notes would be fairly useless, I think, to anybody but me. And even weeks after the fact, if I've worked through something and written about it or done something, I don't always know if it's even worth keeping them because they seem, you know, they're not like a rough draft of Leda and the Swan or something… Yeah…

…..

That's the end of today's podcast episode. I hope that both your body and your mind moved to someplace new since we started. And perhaps you may feel inspired to try a new form of note-taking yourself. Start a commonplace book, draw your own morning mandalas, collage vintage paper into new art.

You can watch the full version of my conversation with Jillian Hess in the videos section of the WriteSPACE Library. That's my online membership community at helensword.com.

Thanks for listening, and I look forward to walking with you again soon.