A metaphor is like . . . a double-decker bus careening wildly through the air while its passengers sit calmly inside?!

Well, I guess that’s as good a metaphor as any for the way metaphor works. Derived from the Greek words meta (over) and pherin (carry), metaphor is a figure of language that draws unexpected connections between seemingly unrelated objects or ideas; it carries us over from one conceptual space into another. Most of the time, the journey is so smooth that we don’t even notice how high we’re flying or how far we’ve travelled. But every now and then, when a metaphor stretches our senses or lurches out of control, we may feel a sense of vertigo.

Metaphors aren’t just frivolous froufrou, the rarified domain of literary scholars and poets. In Metaphors We Live By — one of my favorite books on metaphor — philosophers of language George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue that all language is deeply metaphorical. The vocabulary of embodied experience is (metaphorically) hardwired into our brains, which explains why we tend to talk about abstract concepts such as time (“the hours are slipping away”) and intellect (“I’m gathering my thoughts”) as though they were material objects.

Still not convinced? I challenge you (whoops, challenge is a metaphor!) to write a whole paragraph on any abstract topic without employing (whoops again) any metaphorical language. Chances are that you won’t get very far (whoops again) — or if you do manage to come up with more than a few metaphor-free sentences, your writing will be as bland as dry toast without butter or jam.

For me, metaphor is a magic bus that I plan to keep riding for as long as I keep writing. It’s been quite a journey so far! I’ve published a number of articles and book chapters on the explanatory, generative, and redemptive powers of metaphor, and that bus is still a long way from running out of gas. Below is an omnibus (pun intended) of lightly adapted excerpts.

Enjoy!

Show and tell (2012)

The fact is, that in the primeval struggle of the jungle, as in the refinements of civilized warfare, we see in progress a great evolutionary armament race. . . . Just as greater speed in the pursued has developed in relation to increased speed in the pursuer; or defensive armour in relation to aggressive weapons; so the perfection of concealing devices has evolved in response to increased powers of perception.

H. B. Cott, Adaptive Coloration in Animals (London: Metheun, 1940), 158-9.

Cott’s “evolutionary arms race” analogy — animal species are like nations at war, heightened perception is like a weapon, camouflaging devices are like defensive armor — belongs to a long list of analogies that scientists and scholars have used to help us make sense of our world. Computer programmers “boot” their hard drives (the term derives from the phrase “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps”); linguists who study metaphor and analogy speak of “conceptual mappings.” Some of these analogies may be misleading: for example, so-called “junk DNA,” which denotes non-coding portions of a genome sequence, has turned out to have more important biological functions than its throwaway name would suggest. Many scientific analogies, however, are so effective and compelling that they have entered our cultural lexicon and perhaps our very consciousness. The programmer who first slapped familiar office labels onto various computer functions — “desktop,” “file,” “folder,” “control panel,” “recycle bin” — certainly knew something about human psychology and our hunger for language that invokes the physical realm.

from Helen Sword, Stylish Academic Writing (Harvard University Press, 2012)

Metaphors to write by (2017)

If you here require a practical rule of me, I will present you with this: Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it — wholeheartedly — and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.

Arthur Quiller-Couch, “On Style,” 1914

If you want a golden rule that will fit every thing, this is it: Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.

William Morris, “The Beauty of Life,” 1919

If editing is akin to infanticide, what other acts of violence and sacrifice does our writing demand of us? Arthur Quiller-Couch’s murderous metaphor has been quoted, misquoted, and misattributed by numerous authors, but seldom with any commentary to the effect that its morbid view of the writer’s craft might cause far worse damage than the demise of a few overblown sentences. What if we were to replace Quiller-Couch’s “practical rule” for writing with William Morris’s “golden rule” for living, which teaches us that practicality and beauty can be soul mates rather than enemies? What happens when we invite positive emotions and language into our writing practice — and encourage them to make themselves at home?

from Helen Sword, Air & Light & Time & Space: How Successful Academics Write (Harvard University Press, 2017)

Mining the language of metaphor (2018)

In my research on the background, habits, and emotions of academic writers from across the disciplines and around the world, I found metaphorical language everywhere. How do academics learn to write?

By the seat of my pants.

Sink or swim.

How do they get their writing done?

Fifteen minute jam sessions.

My writing comes in waves.

How do they feel about their writing?

Writing is like going to bed as a child— I resist it constantly.

The road to satisfaction is paved with less enjoyable emotions.

Each of these phrases contains shadings and highlights that get flattened out in the conceptual glare of abstractions such as anxiety or pleasure. Even apparently positive metaphors nearly always reveal a negative face, a “shadow side” that lends them dimension and meaning:

I love to immerse myself.

(But immersion can lead to drowning).

I always know I’ll get to lift off.

(But until you do, you’re stuck on the ground).

The most complex and productive metaphors chart an author’s progress from blockage to breakthrough in ways that acknowledge both the challenges and the pleasures of the process:

I enjoy being lost and hacking away the bush and branches to reach the clearing,

[It’s] akin to a really good cardio work-out.

Some respondents even convey the intricacies of their ambivalence in phrases that have the sonorous ring of poetry:

I walk my thoughts together in the forest.

It feels like jumping into a river.

Words are like gold.

from Helen Sword, Marion Blumenstein, Alistair Kwan, Louisa Shen & Evija Trofimova, Seven Ways of Looking at a Data Set (Qualitative Inquiry, 27:4 (2018): 499-508)

Metaphors of frustration (2018)

When I asked a group of colleagues at a writing retreat to come up with metaphors that describe their frustration as writers, their words (paradoxically?) flowed freely. Frustration, they told us, resembles a physical blockage, like constipation or being unable to sneeze. Frustration is an impassable obstacle, like coming to the edge of a cliff. Frustration is an expenditure of energy that gets you nowhere, like running in a hamster wheel. Frustration is a self-imposed hindrance, like painting yourself into a corner. Frustration is a road paved with broken glass: “Whichever way you go, it’s going to be painful.” Frustration is performance anxiety, like getting on stage and forgetting your lines. Frustration is a heaviness, like being weighted down by stones. Frustration is slow progress, like a snail inching its way across a playground. Frustration is fear, like a dream of having your teeth fall out. Frustration is the distance between you and your destination, like a light at the end of the tunnel that never seems to get any closer. Frustration is an exercise in futility, like playing an endless game of Snakes and Ladders or winning a pie-eating contest in which the prize is more pie. Frustration is the panic you feel when you are in an impenetrable wilderness and find out that even your guide is lost.

Three months later, I prompted the same group of colleagues to “re-story” their metaphors of frustration into redemptive tales of effort and accomplishment. Some found ways of conquering frustration by enlisting other people to help them:

If you’re afraid of forgetting your lines, you can make sure there’s a prompter in the wings of the theatre.

Sometimes when I feel that I’m sinking in a swamp, all it takes to save me is a lifeline thrown by a friend or colleague.

Some invoked metaphors of patience:

When you’re being swept out to sea by a riptide, there’s no point fighting it; you just need to stay afloat and swim sideways until you’re free of the current.

It’s like those Biblical stories of walking through a dark place but knowing you’ll survive: transformation requires faith.

Some called on magical thinking:

In fairy tales, if you find yourself trapped underwater, you’ll sprout gills and turn into a fish or a mermaid.

When you come to the edge of the cliff, just fly!

What all of these solutions have in common is a shift of attitude: what one colleague called “crossing the bridge from the can’t to the can.” Metaphor, as this exercise reminds us, can become a tool not just for describing frustration but for refashioning it, rerouting it, and finding a way beyond it.

from Helen Sword, Evija Trofimova & Madeleine Ballard, Frustrated Academic Writers (Higher Education Research and Development, 37:4, 2018)

The feedback loop (2019)

Metaphor can exercise a powerful “feedback effect” on our psyches, shaping how we think and act:

In all aspects of life ... we define our reality in terms of metaphors and then proceed to act on the basis of the metaphors. (Lakoff & Johnson, Metaphors We Live By ).

My own “aha moment” in this regard occurred when I was working on a book about the writing habits of successful academics, a project that inevitably prompted considerable self-reflection. I wanted my book to inspire academics to write with greater confidence, craftsmanship, and care. However, an early reader of the manuscript pointed out that I described my own confident, craft-focused, careful compositional style as finicky, snail-paced, and pathetically slow. The negative feedback generated by my choice of words, I realized, was at odds with the positive image of the writing process that I aspired to project. Thanks to my reader’s gentle intervention, I replaced pathologizing verbs such as fuss, fiddle, and tweak with craft-affirming alternatives such as adjust, tinker, and polish — and from that moment onward I resolved to take greater care with my metaphors.

from Helen Sword, Snowflakes, Splinters, and Cobblestones: Metaphors for Writing (in S. Farquhar and E. Fitzpatrick, eds., Narrative and Metaphor: Innovative Methodologies and Practice, Springer, 2019)

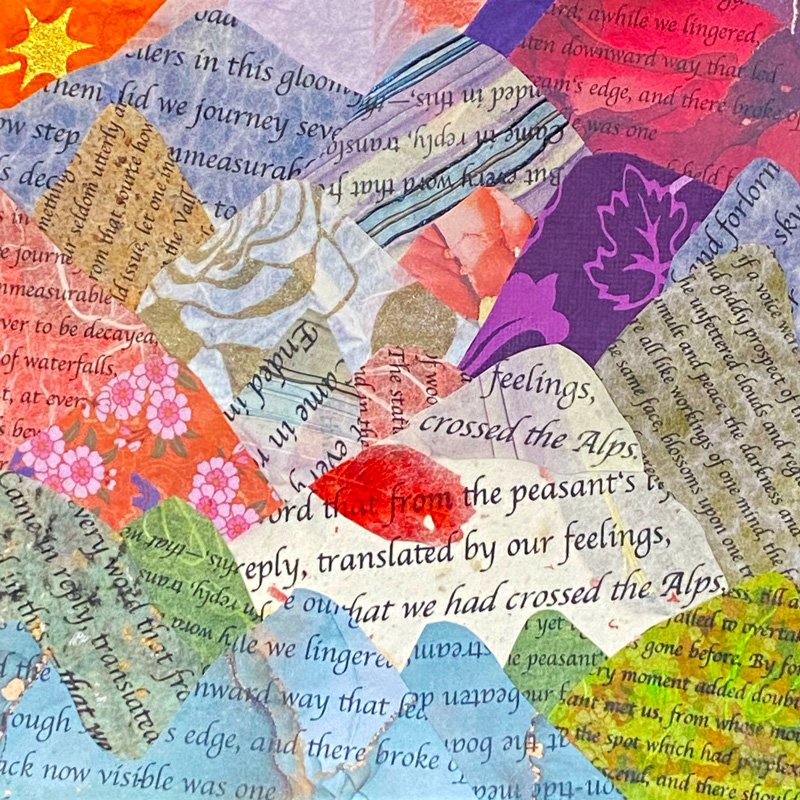

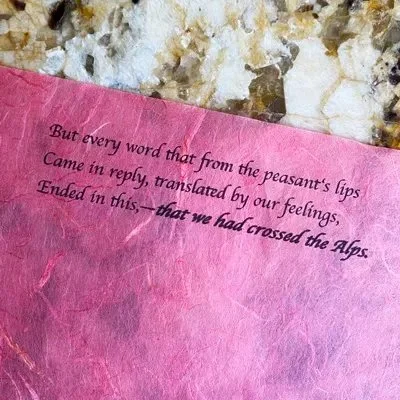

The mosaic path (2022)

I love collecting objects that have been discarded or passed over by others – stained glass offcuts, chipped crockery, river stones, seashells – and assembling them into new works of art, creating unexpected juxtapositions of color and form. When the intricate mosaic walkway that I had spent seven years designing and grouting into place was bulldozed by autocratic university administrators and replaced with a straight and narrow footpath, I understood their motivation: my joyfully meandering pathway was too non-conformist, its colors too rich, its energy too vibrant, to suit their dehumanizing neoliberal agenda. But a mosaic, having been created from fragments, can be reassembled in new configurations even after having been blown apart. I now spend my days on a beautiful South Pacific island laying out another crazy paving, this one even more colorful and playful than the last. (It’s called the WriteSPACE). This time, however, the pathway runs through my own property rather than the university’s; never again will I risk having my life and art consigned to a dumpster by philistine landlords.

The mosaic metaphor has helped me recognize my former role as the director of a higher education research centre — indeed, my entire scholarly career — as a creative practice that, like all art-making, is richly fulfilling but fraught with risk. I do not mean to suggest here that metaphorical language can always pave over pain, nor that beleaguered academics should respond to all administrative abuses of power as I have done in this instance, by retreating to an island (literally as well figuratively) and giving up on institutional activism. My decision to start my own business as an international writing consultant, building new pathways into writing for scholars around the world, has come towards the end of a long career spent fighting in the university trenches for causes such as gender equity, cultural inclusiveness, and student-centered teaching.

If I were ten years younger, a different set of metaphors might have inspired me to gird my loins emotionally and return to the fray. (Rest assured, however, that I would not have persisted with the military trope for long; its shadow side is too dark to dwell in, even if academic life does sometimes feel like a war zone.) Either way, redemptive metaphors have helped me find my way forward. Indeed, the very process of writing this essay has accelerated my transformation from a self-perceived victim of circumstance to a maker and shaper who has taken my future into my own hands.

from Helen Sword, Diving Deeper: The Redemptive Power of Metaphor (in Julie Hansen & Ingela Nilsson, eds, Critical Storytelling: Experiences of Power Abuse in Academia, Brill, 2022)

The SPACE of metaphor (2023)

A well-turned metaphor can be a source of pleasure in its own right. But metaphors can also amplify our pleasure in writing, casting light into the darkest corners of our WriteSPACE and helping us negotiate its challenges. By rendering abstract emotions concrete, metaphors give shape and substance to our fears, hopes, and desires. At their most generative, they become the emotional touchstones that we return to again and again, the guides and mentors that lead us onward and inward to new discoveries and deeper truths about our writing.

from Helen Sword, Writing with Pleasure (Princeton University Press, 2023)

This post was originally published on my free Substack newsletter, Helen’s Word. Subscribe here to access my full Substack archive and get weekly writing-related news and inspiration delivered straight to your inbox.

WriteSPACE members enjoy a complimentary subscription to Helen’s Word as part of their membership, which costs just USD $12.50 per month on the annual plan. Not a member? Sign up now for a free 30-day trial!